Up to No Good

© Dave Needham, 2019

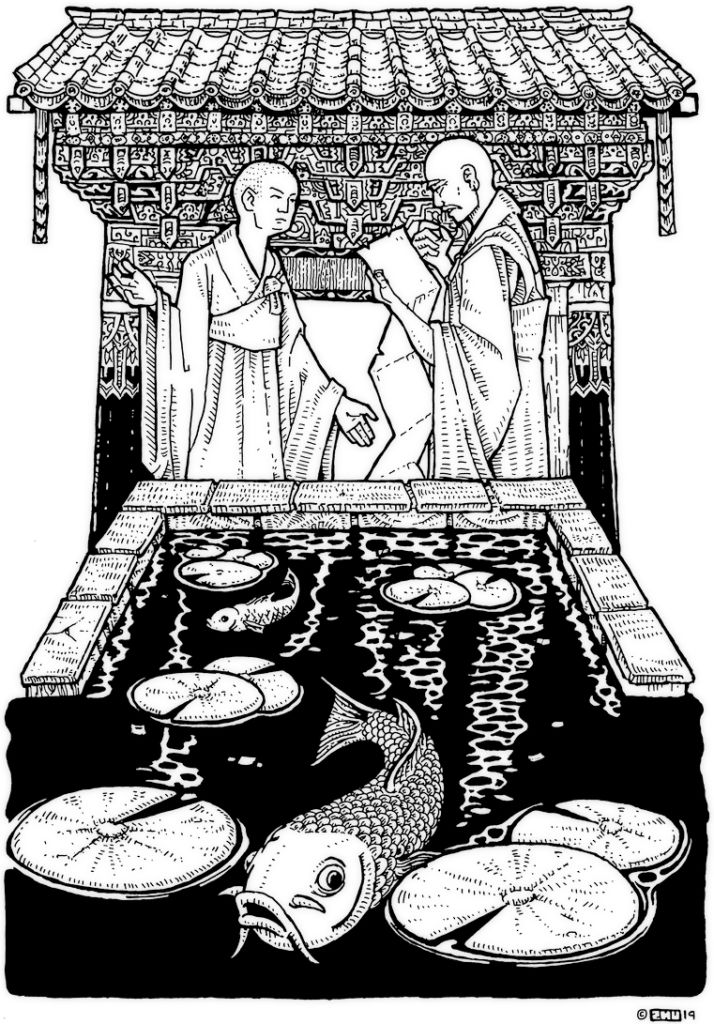

Illustration for the 49th case.

This is a strange time of year. After the joy, stress and activity of Christmas, we settle into deep quiet of winter. It’s a trying time for a lot of people, with the lack of sun and the ever-present slush. But it’s also a precious season if we can only see it for what it is. The short, dim days and the long cold nights are the best time to try your hand at the highest and most difficult of Zen practices — this is the practice of doing nothing.

A monk once asked the great 10th century Zen Master Zhaozhou, “What is true meditation?”

Zhaozhou said, “It is non-meditation.”

The monk then said, “What is non-meditation?”

Zhaozhou said, “It lives! It lives!”

Meditation is a wonderful practice – as I’ve told you in this class, it is the practice of just being aware of the present moment and seeing what happens – without goals or expectations. But as wonderful as it is, there is one problem with meditation — it is still doing something. You are deliberately sitting in a meditation posture, excising your awareness and letting go of thoughts. In the dialogue with the monk, Zhaozhou is telling us that there’s an even deeper practice — doing nothing at all.

We are not used to doing nothing at all. And because we’re not used to it, we often misunderstand it. Doing nothing does not mean wasting time or procrastination. Wasting time is something, even if that something merely means the persistent avoidance of something else. Doing nothing does not even mean resting or daydreaming. Doing nothing is nothing. It’s not watching cat videos, and it’s not lazing in bed. Not that I’m knocking cat videos or napping – I enjoy both. But they are easy to do and don’t require much Zen training.

Doing nothing is challenging. You prepare for this challenge though your meditation practice. The Zen art of doing nothing means that you are not amusing yourself or enriching yourself. You are not thinking and you are not thoughtless. You are not creating and you are not destroying. You are not casting away stones and you are not gathering stones together. In such a state, you are perfectly balanced between form and emptiness. The form comes from the fact that you are doing. The emptiness comes from the fact that you are doing nothing.

What’s the good of doing nothing? That’s like asking, what’s the good of going home. Maybe there is no good, and yet it makes us a more authentic person when we return to the place from where we arose.

I recently finished a big project — a book that took years to write. In the past after, I’ve gotten depressed after completing big projects — the depression sucks, but it’s a relatively common reaction because without sense of purpose and urgency we get from our goals, we can feel directionless. This sense of deflation has even got a name: “post-achievement depression”. This time, however, after finishing my book, I didn’t get depressed because I tried something new. I actively pursued doing nothing. I felt, and gave into, this powerful pull to just sit on my couch. Sometimes I would cheat and mix a little something in with all the nothing — I would stare at a lava-lamp, or listen to audiobooks by Anthony Trollope, which is the closest thing to nothing that something can be.

It has been several weeks now and still all I really want to do is nothing. And I’m happy with that. At this season, it’s helpful to look at all the trees around us. They seem lifeless and leafless and all the sap is frozen in the limbs. And yet they are alive. Trees don’t need to be told that they flourish in cycles of beautiful growth and cold stasis. And so it is with us. Our times of doing nothing — of what Zhaozhou called “non-meditation” — are a natural part of our own cycle, if we can only relearn it. And then we see what Zhaozhou saw. Non-meditation can seem like a waste of time, but, the truth is, as he said, “It lives! It lives!”

So try it for yourselves this winter. Build up to non-meditation with a healthy diet of meditation-meditation. And then, when you are ready, take a deep breath and start doing nothing.

January 2020