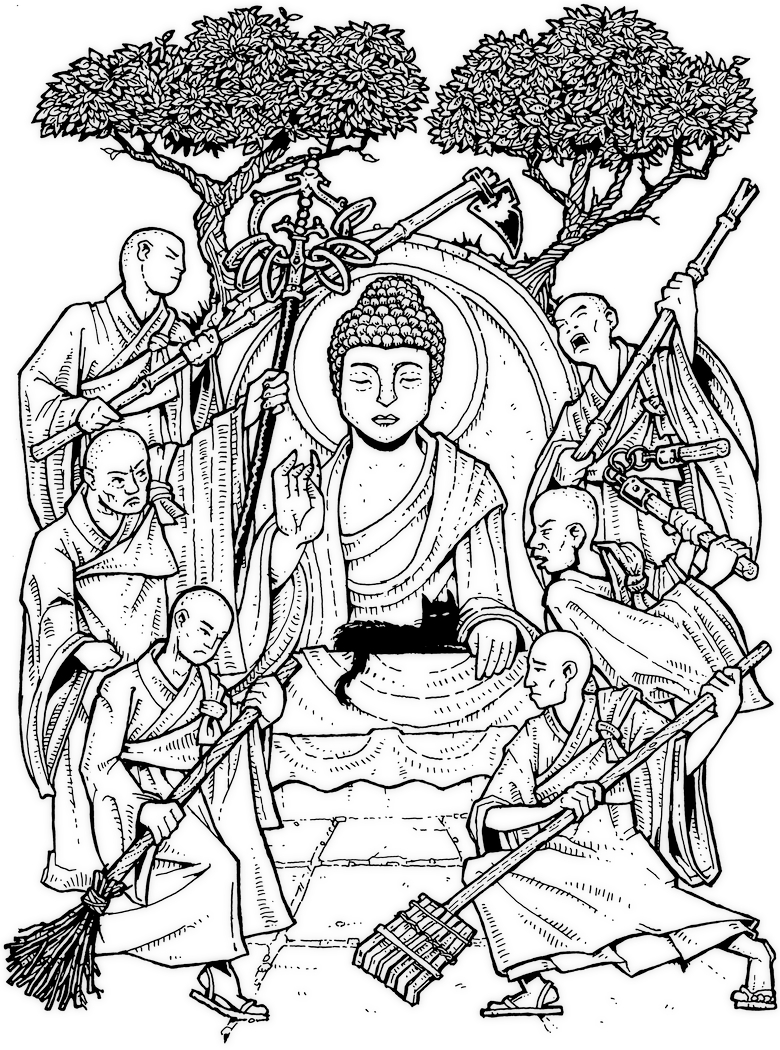

Spitting on the Buddha

© Dave Needham, 2019

Illustration for the 63rd case.

The other day I was on the phone with a new friend of mine – a Zen Master in the Korean tradition who lives in the Bronx. He told me a story I’d never heard before about the historical Buddha, who lived in Northern India about 2500 years ago. The story goes like this:

Thus I have heard that on one occasion the Buddha, the Blessed One was staying near Savatthi in Jeta’s Grove. On that occasion, the Buddha was sitting under a tree when a approached and spat in his face. The Buddha, the Blessed One, wiped it off, and he asked the man, “What next? What do you want to say next?” The man was puzzled because expected the Buddha to become angry or fearful or to react in some way.

But Buddha’s disciples became angry, and they reacted. His closest disciple, Ananda, said, “This is too much. We cannot tolerate it. He has to be punished for it, otherwise the Buddha, the World Honored One, will not be safe.”

Buddha said, “He has not offended me. He is a stranger. He must have heard from people about me. And he may have formed some idea, a notion of me. He has not spit on me, he has spit on his notion. If you think on it deeply, he has spit on his own mind. I am not part of it.”

Puzzled, confused, the man returned home. He could not sleep the whole night. That night in bed he tossed and turned, thinking over what the Buddha had said. The next morning he returned to Jeta’s Grove and bowed to the Buddha and supplicated him for forgiveness.

The Buddha said, “The Ganges goes on flowing, it is never the same Ganges again. Every person is a river. The man you spit upon is no longer here. I look just like him, but I am not the same – The river has flowed so much. I cannot forgive you because I have no grudge against you. And you also are new. I can see you are not the same man who came yesterday because that man was angry and he spat, whereas you are bowing at my feet, touching my feet. How can you be the same? The man who spit and the man on whom he spit are no more. Come closer. Let us talk of something else.”

And that’s the story. There are two things striking about it. First, I find the Buddha’s reaction to being spit on very beautiful. It gets at a great truth: when people approach us with hostility or accusations, they are generally not reacting to who we really are: they are reacting to their own image of who we are.

Indeed, that’s one of the things that’s most upsetting: no one likes being spit on, but what’s even more threatening is when someone else tries to coopt you into their own imaginary view of you. You were crossing at a traffic light and a driver starts honking and yelling at you. You get offended not just because of the honking, but because it makes you feel as though you did something wrong. There’s a horrible friction between the real you, who was crossing at the light, and this new, imaginary and careless you created by the misperception of the driver.

In this story, the Buddha cuts through this tension. He doesn’t identify in any way with the imaginary Buddha created in the mind of the spitting man. He deliberately and thoughtfully disavows that illusionary Buddha, and so it’s hard for him to become upset. That’s a lesson for us all – it’s certainly a lesson for me. I’ve found that life becomes a lot less upsetting if, when strangers spit at me, or honk at me, or upbraid me, I deliberately and thoughtfully keep in mind that they are probably honking at an imaginary Matthew. As the Buddha says, “I am not part of it.”

But there’s a second striking thing about this story. And that’s why my friend told it to me. It’s that this story is entirely made up — it was invented a few decades ago by Rajneesh (also known as Osho), an Indian guru with a taste for Rolls Royces who died in the 1990’s.

And I think there is a beautiful lesson there too. The story is a fantasy and it exposes our own fantasies. Our idea of a perfect Buddha who never gets angry really boils down to the idea that there is a perfect version of Matthew or a perfect version of yourself who also never gets angry. When you want to be that perfect being, it causes a horrible friction between the real you (who often does get angry) and this imaginary you (who never reacts, or yells, or feels hurt).

But that perfect Buddha is just an invention of a self-appointed guru with 97 Rolls Royces. It’s an illusion. As the Buddha might say, “I am not part of it.”

Where’s the real you? You will approach it when you sit and watch your breath. In the present moment, when you let go of thoughts, you get to escape the imaginary world. What will you find? I don’t know. But I can tell you this: it’s not perfect, but it’s not imperfect either.

August 2019